|

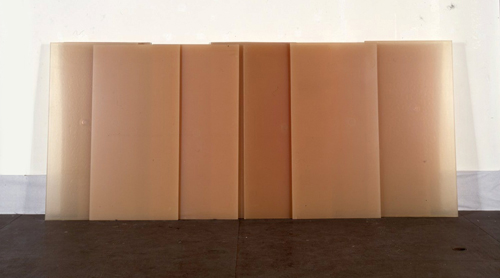

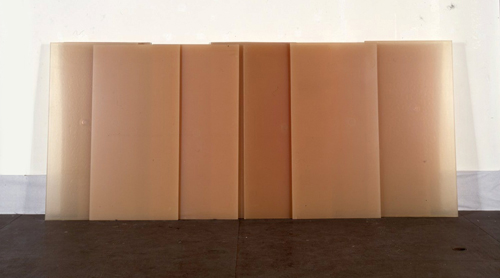

Seungtaik Jang does not paint monochromes, even if his paintings are always in just one color, In fact, Jang does not really paint at all, since a paintbrush never touches the surface of his works. He congeals color in resin or, more exactly, congeals color with resin. Thus, color is never a coating laid on a support; it is a block of color immobilized in front of the viewer.

The ghost of color

Color is not, of course, a material substance; it needs a physical object to give it a body, to give it materiality. Color is transported by light and takes form on the surface of objects. With his paintings-for lack of a better word we will continue to refer to them in this way-1ight and color become fully corporeal, since light and color alone give form to a transparent substance, resin. We thus find ourselves

faced with a disturbing fact: two things, neither of which has a material body, become visible by being mixed together. But what is particularly troubling is that the color remains intangible; it is not truly color but the ghost of color. Color is not, of course, a material substance; it needs a physical object to give it a body, to give it materiality. Color is transported by light and takes form on the surface of objects. With his paintings-for lack of a better word we will continue to refer to them in this way-1ight and color become fully corporeal, since light and color alone give form to a transparent substance, resin. We thus find ourselves

faced with a disturbing fact: two things, neither of which has a material body, become visible by being mixed together. But what is particularly troubling is that the color remains intangible; it is not truly color but the ghost of color.

Congealed time

So these are not monochromes, but bodies that reveal color and light. The fact that there is but a single color is a technical aspect of the work, but never its aim or its purpose. Jang never reduces painting to color, as Robert Mangold, Brice Marden, Alan Charlton and many others have done. Instead, he is interested in displaying a principle of immobility and a principle of circulation. Color is congealed, but light, instead of simply being reflected by the material, passes through it, strikes the

wall, and then comes back through this same material. Light thus circulates in two directions, giving the impression that it is emanating from the object itself and not from the exterior. This is undoubtedly the most troubling aspect of these works, since we are made to believe that the object is giving off its own light, that it is radiant, In contrast to this movement stands the immobility of the color, which seems congealed, forever frozen in a block, in a sheath, like a fossil.

The paintings are thus figures of time: between immobile, petrified time and mobile, flowing time there exists the time of the work. I have one of Jang's works, and I have had the opportunity to observe this strange phenomenon: the work is always itself, always imbued with something of a secret identity; yet, at the same time, it changes constantly under the action of the movement, brilliance, and color of light.

A small, portable cosmogony

But this work is not only phenomenological. Jang's painting differs radicallyfrom James Turrel or Ettore Spalletti's, for example. The first artist wants the viewer to perceive color as though it were a solid object; he seeks to submerge the viewer in an improbable space and to transform him into an observer of a physical phenomenon that exceeds the limits of his perception. In the work of the Italian, Spalletti, color becomes an object without drawing, without contour, continually going beyond the form

which could enclose it. Apart from these poetic, indeed eminently poetic, elements, nothing else nourishes the work. Seungtaik Jang, on the other hand, puts us face to face not only with color and light, but also with the material world. Whether the resin is worked with fire or used to trap drops of water, whether the surface of the work is transparent or opaque (suggesting ice or air), it is the very substance of the world that has been captured. Jang never separates the perception of the work perception of

reality. He transforms nature into a work, that is into an artifact. As we know, an artifact is a false object that imitates the world but it is also a result of art.

His art is tragic because of this- because it is a moment of the world frozen in an improbable object. And this means his work is not in the least peaceful, regardless of appearances: it embodies the world's tumult dominated but near to bursting out once again, as though it were a modem Pandora's box.

1995

|

Color is not, of course, a material substance; it needs a physical object to give it a body, to give it materiality. Color is transported by light and takes form on the surface of objects. With his paintings-for lack of a better word we will continue to refer to them in this way-1ight and color become fully corporeal, since light and color alone give form to a transparent substance, resin. We thus find ourselves

faced with a disturbing fact: two things, neither of which has a material body, become visible by being mixed together. But what is particularly troubling is that the color remains intangible; it is not truly color but the ghost of color.

Color is not, of course, a material substance; it needs a physical object to give it a body, to give it materiality. Color is transported by light and takes form on the surface of objects. With his paintings-for lack of a better word we will continue to refer to them in this way-1ight and color become fully corporeal, since light and color alone give form to a transparent substance, resin. We thus find ourselves

faced with a disturbing fact: two things, neither of which has a material body, become visible by being mixed together. But what is particularly troubling is that the color remains intangible; it is not truly color but the ghost of color.