|

Poly Painting that Aims at the Skin of Painting |

|

Kho Chung-hwan / art critic |

|

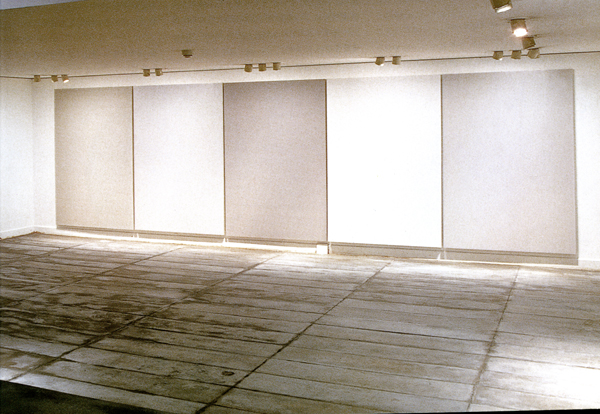

Seungtaik Jang had a solo exhibition in Seoul in 1990, when he was still studying in France. The title of the exhibition was “Monument for Those Who are Deeply in Despair.” It was an exhibition by which the thirty-one year-old Jang paid tribute to his father, who had passed away twenty-seven years earlier at the age of thirty-one. It was a discovery of a self that overlaps at the age of thirty-one, and this discovery was something ironic in which changeable and unchangeable factors overlap. This makes one feel that the conscience of the artist desires something very fundamental, permanent, long lasting, and absolute that goes beyond the changes of time and space. Thus, the despair means something changeable and, by doing so, he monumentalized himself, who changed and despaired. Such a realization might have led him to pursue something more fundamental within his artistic practice than the apparent phenomenon before one’s eyes. Medial Space and Transparent Cognizance An interest in materiality within the artist’s work becomes the motivation for turning away from illusionistic painting toward constructive painting that is closer to objects themselves. The flat dimensionality is still maintained, as a fundamental condition of painting, yet the essential surface shifts to a surface with three-dimensionality and a certain amount of thickness and property, and the materiality of the subject replaces painting. Since the 1991 exhibition, until 1993, Jang concentrated on making experimental works that explored the permanent nature of certain matter. When examining the works made under the themes “medial space” and “transparent cognizance”, “medial space” means empty space that doesn’t mean anything, that lacks particular messages and significance that typically accompany representational paintings, and “transparent cognizance” aims at sub-consciousness rather than consciousness, referring to the transparent boundaries of mind that direct potential painterly sensibility and possibility. The transparent boundary of such a cognizance employs the process of physical activities such as burning, sooting, boiling, melting, pouring, and firming within the forming process, utilizing the physical properties of the transparent and semi-transparent materials of resin and paraffin and their resultant immediacy. Such tasks by the artist remind one of the pseudo-science of an alchemist who aspired himself through the amalgam of the four elements – water, fire, earth, and air. Through pseudo-science and illusionistic activity, the artist sensitized the nature of the material. The transparency of the resin and the soft, tactile nature of the paraffin appeal to the eye of the viewer. Factors such as the transparent and tactile character of materials and the injection of meaning through physical action upon the material become important determinants of the direction of the artist. Solidification of Light and Color Dislocation of Painting By adding oil to the surface of Plexiglas, the artist internalizes the layered touch, which is the essentiality of painting, along with its flatness. Yet, more tactile and sensorial physical labors are brought to the work, as he uses his palm standing on its side like a knife, brushing down the colors beneath it. Additionally, a surface that employs a small roller designed for printmaking allows him to achieve an even tone throughout, as if surveying the entire work. Moreover, it’ is meant to remind us of pure consciousness, pure sense, or even pure concept itself. Although the appearance may be similar in each work, this underlies the artist’s desire for change in and throughout each work. Such an attempt should not be taken to be beyond ubiquity at the surface level, but rather, the result of the artist’s sensorial response toward the subtle transformation where light, color, and materials mutually encounter one another. On the other hand, the artist attempts at tediously cutting his work, which betrays the concept of drawing as if looking at small waves of water, cresting into the tableau. Such fine holes turn the box-like, three-dimensional volume—along with its semi-translucent colors and the painterly surface—into a screen of liquid immersed within the consistency of its frames. The elements of liquid and holes cause us to recall the unreality that belies reality, deep within the inner self; an unconsciousness that brings consciousness to oneself; and a pond Narcissus does of oblivion that sinks—like Narcissus, whom we are like—into in the memory of oneself. Although there is a point from which all changeable things derive that feels as though one is looking at an archetype that does not change itself.

The central factor in Jang’s work is, first and foremost, the semi-translucent color that reveals what is inside. Such a sense of color emits a particular aura. The colors penetrate the inner surface of the work, rather than remaining on top. Such color that penetrates the inner material is not different from the character of light, in fact. Paraffin, resin mass, and translucent light within multi-layered Plexiglas trap the light within itself. As a result, the artist’s work becomes a unifying mass, where colors, light, and materials come together. The artist’s sensibility about the colors that are also lights themselves is located in the boundary between the translucent light that reveals the inside of a thing (symbolizing truth toward the sensorial phenomenon) and opaque colors that operate only on the surface of a thing (symbolizing the dual thought that separates surface from inner depth). The artist indicates such a boundary as an “ambiguous boundary,” which implies not only physical phenomena between colors and light, but also the psychological boundary symbolized by color and light. Above all, it means the artist’s sensibility in response to the phenomena of color and light. If the sensibility of the artist were to be compared with color, it would be closer to the semi-transparent milky light of introspectiveness, despite the infinity of the many galaxies that it evokes. Yet, this milky light differs from normative, conceptual color, which carries things into the inner self, as well as the flamboyant primary colors that amuse the senses. Nevertheless, the milky colors respond to delicate sensitivity due to their particular ambiguous boundary. For instance, it is a potential world-like “sky light at dawn encountered with the ground,” or “light around the sun during a solar eclipse,” or “translucent light of nails of an immature girl,” compared to our boring, phenomenal world –these are nonetheless clues that, descriptively, reveal something. Jang’s works transform the flatness of dry painting into the liquid, tactile, even, sensual skin of the feel of the otherwise dead and dry canvas. “I don’t make paintings that are monochrome in the narrow sense of the word. Because I don’t work with only one color. I solidify colors within the resin. Light and color become one through the resin, making the viewer believe that the paint can emit its own light.”

“The tragedy of my work is that it depends on the moment when the world becomes frozen within the subject. Despite the gentle appearance of my work, it is not calm. It is a Pandora’s Box. It is as if a repressed world within is about to explode.” Seungtaik Jang was born in Goyang, Gyungie-do in 1959. After graduating from the Department of Western Painting at Hong-ik University in 1986, Jang went to France, where he graduated from the Department of Painting at Ecole Nationale Supreieure des Arts Decoratifs in 1989, and received a Graduate Diploma from Pantheon-Sorbonne. Jang’s work has appeared in eleven solo exhibitions, He has contributed work to numerous group exhibitions, including Art and Space (Gallery Hundai, 2001), Lottery of Painting (National Contemporary Art Museum, 2001), and Contemporary Art of Korea and Japan (Gwangju Biennale, 2000). Translation Hyewon Yi Published in Art in Culture, May 2002 |

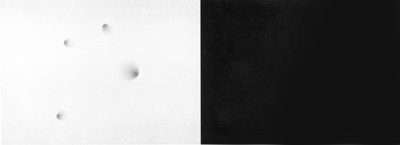

Compared with his later works, Jang’s work at the time consists of two-dimensional painting, occasionally following the conventional concept of painting by making pictures. However, whether they are paintings or objects, they are not concerned with specific subjects. Instead, what is dominant is abstraction by way of accidental and painterly effect. This reminds one of ink abstract paintings, as though abstract

shapes were dispersed freely over the surface, and it is like looking at a dynamic scene where light and dark, order and chaos, cross as opposite poles of existence and symbols of an inner mind. It is self-reflective and self-intuitive, as if enduring the darkness of being from the inner abyss. In addition, it couples with his interest in injecting active meaning into accidental spontaneity and physical property of the material of painting through stain and blotting effects.

Compared with his later works, Jang’s work at the time consists of two-dimensional painting, occasionally following the conventional concept of painting by making pictures. However, whether they are paintings or objects, they are not concerned with specific subjects. Instead, what is dominant is abstraction by way of accidental and painterly effect. This reminds one of ink abstract paintings, as though abstract

shapes were dispersed freely over the surface, and it is like looking at a dynamic scene where light and dark, order and chaos, cross as opposite poles of existence and symbols of an inner mind. It is self-reflective and self-intuitive, as if enduring the darkness of being from the inner abyss. In addition, it couples with his interest in injecting active meaning into accidental spontaneity and physical property of the material of painting through stain and blotting effects.